“Tó’éí’iina means our water is life—it sustains us and provides for our livestock, rejuvenates our cornfields, and strengthens us as human beings.”

Chairman Rickie Nez (T’iistsoh Sikaad, Nenahnezad, Upper Fruitland, Tsé Daa K’aan, Newcomb, San Juan)

Nicknamed the “Basin of Contention,” the Colorado River system is notoriously the most litigated and legislated basin in the United States. The Colorado River Compact—the primary treaty governing the basin among the seven U.S. basin states—expires in 2026, offering an opportunity to rethink the governance of the basin for the first time in over a century. Strengthening tribal water rights will be fundamentally important for the new framework to equitably and effectively serve the needs of all stakeholders in the Basin.

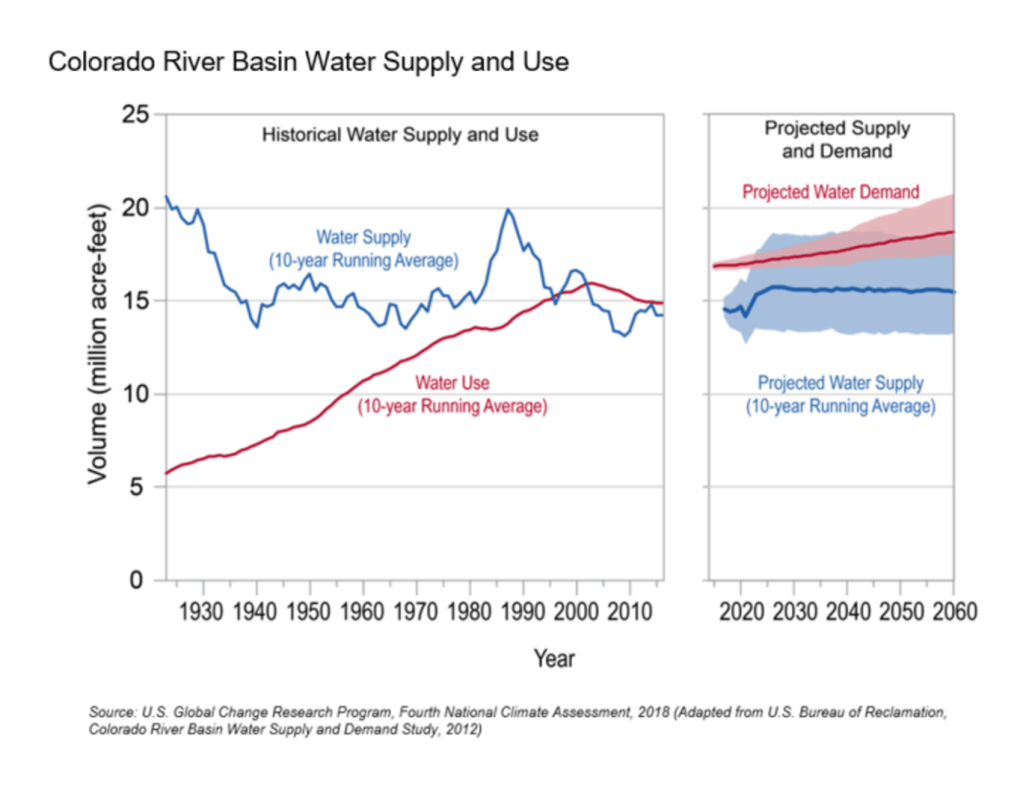

Flowing through a rugged and rich landscape, the Colorado River Basin spans approximately 240,000 square miles of mountains, canyons, deserts, and prairies. The Colorado River Basin is the lifeblood of much of the American West, catching precious precipitation and directing snowmelt to sustain the human and natural ecosystems that depend on its rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and groundwaters. For the last twenty-two years, the southwestern United States have been under a drought that continues to this day. Between 17% and 54% of runoff loss since 2000 can be attributed to climate warming.

Even without a climate emergency creating drought conditions, the basin already had a logistical problem: overallocation. A century’s worth of laws and documents dubbed the “Law of the River” determine how much water can be allocated to each state. When these allocations were established a century ago, they greatly overestimated how much water would flow through the basin and underestimated the future demand on the water supply. Today, the Colorado River system supplies water to over 40 million people throughout two countries, seven states, thirty tribes, and two Mexican states.

Water rights in the American West are based on “first in time, first in right,” or in other words, “first come, first serve.” As the oldest members of the Colorado River Basin, indigenous nations hold the strongest water rights; however, basin tribes currently only divert half of their existing rights. A variety of factors have made it difficult to use their water claims.

Barriers to Indigenous participation

Historically, decision-makers have perpetuated a narrative of tribes as “outside parties” and discouraged collaboration between states and tribal leaders. This status quo, in many ways, favors the states. For example, California has, for many years, used more than its allotted share, taking advantage of unused water flowing through Indian reservations, where water rights are underutilized (Adler, 2008). A power-balancing shift toward developing tribal water rights will mean that states like California can no longer depend on that “surplus” water.

One of the widest gaps between an equitable future basin is in a lack of understanding of the ways in which tribes manage their water allocations and perceive future plans, yet data sharing can be a valuable tool for facilitating transboundary water management. Toward bridging this gap, the Bureau of Reclamation and Department of the Interior partnered with the Ten Tribes Partnership—a coalition of ten tribes with recognized water rights in the Colorado River Basin—to conduct the 2018 Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes Partnership Water Study (Tribal Water Study). This 362-page study offers an invaluable overview of the tribes’ challenges, needs, and dreams for the basin and aids basin-wide collaboration. While federal and state governments have put forth promising efforts to increase tribal involvement in decision-making and management, twelve tribes await the full recognition of their claims to Colorado River waters and tribes with existing water rights struggle to develop and maintain adequate infrastructure.

Why is recognition of these rights important?

Infrastructure development on tribal land has been historically delayed by poverty and by the slow legal settlement of water rights. These widespread limitations to accessing water rights and infrastructure directly harm the health and functioning of tribal communities. Obtaining the legal acknowledgement of tribal water rights gives tribes access to greater opportunities to develop infrastructure and put their allotments towards their intended purpose: to enable indigenous peoples to improve their quality of life and to thrive. Without acknowledgement of their water rights, tribes cannot lease out water allocations, qualify for grants and other forms of development aid, plan infrastructure projects, or obtain legal protection of their rightful resources. Reaching a resolution to outstanding claims would benefit other users in the basin, enabling more accurate estimates of basin demands to be calculated and providing greater certainty to all stakeholders in the basin.

As climate change scours the West with drought and the Colorado River Compact approaches its 2026 expiration date, many voices are calling for an updated, or entirely new, version of the agreement that addresses modern day concerns such as climate change, environmental protection, and indigenous rights. Although climate-induced drought continues to compound the imbalance between water demand and supply, some suggest that the worsening conditions on the basin have necessitated creative collaboration between states and tribes. While tensions remain between competing basin interests, a recent upsurge in support for collaborative governance and stakeholder participation seems to be guiding the basin towards more equitable collaboration and away from conflict. Unlike other basin stakeholders that typically have more economically centered priorities, tribal stakeholders include conservation and ecology among their top priorities (Ten Tribes Water Study, 2018). Fortifying and expanding tribal water rights could make it possible for the basin to eventually flourish.

“A seat at the table alone does not guarantee that the voices and perspectives of those actors are heard.”

Karambelkar and Gerlak, 2020

Sources

Adler, Robert W. “Revisiting the Colorado River Compact: Time for a Change.”Journal of Land, Resources & Environmental Law, vol. 28, no. 1, 2008, pp. 19-48.

Bureau of Reclamation. “Technical Report C Water Demand Assessment,” Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study, Dec. 2012.

Central Arizona Project. “Pascua Yaqui Tribe thrives on water management innovation,” 26 Apr., 2021. https://knowyourwaternews.com/pascua-yaqui-tribe-thrives-on-water-management-innovation/. Colorado River Research Group. Tribes and Water in the Colorado River Basin, University of Colorado Law School. June 2016. http://www.coloradoriverresearchgroup.org.

Colorado Water Conservation Board. “Colorado River Basin.” https://cwcb.colorado.gov/colorado-river. Accessed 17 Dec., 2022.

Department of the Interior; Bureau of Reclamation; Ten Tribes Initiative. Colorado River Basin Ten Tribes Partnership Tribal Water Study. 2018.

Department of the Interior. “Tribes to Receive $1.7 Billion from President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to Fulfill Indian Water Rights Settlements,” 22 Feb. 2022. https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/tribes-receive-17-billion-president-bidens-bipartisan-infrastructure-law-fulfill.

Environmental Defense Fund. Groundwater in the Colorado River Basin Story Map. 2019. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/c11f7b5fd50644f098497fc7a430a9df. Accessed 17 Nov., 2022.

Formisano, Paul. “First in Time, First in Right”: Indigenous Self-Determination in the Colorado River Basin.” Review of International American Studies, 14(1), 2021, pp. 153-175.

Karambelkar, Surabhi, and Andrea K. Gerlak. “Collaborative governance and stakeholder participation in the Colorado River Basin: An examination of patterns of inclusion and exclusion.” Natural Resources Journal, vol. 60, no. 1, Wntr 2020, pp. 1-45.

Lukas, Jeff, and Ben Harding. “Current Understanding of Colorado River Basin Climate and Hydrology.” Chap. 2 in Colorado River Basin Climate and Hydrology: State of the Science, edited by J. Lukas and E. Payton, pp. 42-81. Western Water Assessment, University of Colorado Boulder. 2020.

Navajo Nation Council. “The Navajo Utah Water Rights Settlement Act finalized by the Navajo Nation, State of Utah, and the Interior Department.” 2022. https://www.navajonationcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Navajo_Utah_Water_Rights_2022.05.27.pdf

O’Connor, Rachel. “Colorado River Basin story map highlights importance of managing water below the ground,” Groundwater in the Colorado River Basin Story Map. Environmental Defense Fund. 2019. https://blogs.edf.org/growingreturns/2019/10/24/colorado-river-basin-story-map-highlights-importance-of-managing-water-below-the-ground/. Accessed 17 Nov., 2022.

Purvis Lively, Cathy. “COVID-19 in the Navajo Nation Without Access to Running Water.” Voices in Bioethics, vol. 7, 2021.

Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Democratic Staff. “Inflation Reduction Act of 2022: Provisions Supporting Tribes and Native Communities.” 16 Aug., 2022.

Spivak, Daniel S. “The Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan: An Opportunity for Exploring Demand Management Through Integrated And Collaborative Water Planning.” Natural Resources Journal, vol. 61, no. 2, summer 2021, pp. 173-203.

Water and Tribes Initiative. “Toward a Sense of the Basin: Designing a Collaborative Process to Develop the Next Set of Guidelines for the Colorado River System.” 2020.